ecila Malmstrom publicly speaks of torture. On October 4, when the European politician stood up in parliament to give her support for laws banning the export of items used for implementing the death penalty, there should have been little controversy.

But when footage of her speech was posted online, nobody saw it. YouTube removed the video, which had been uploaded by fellow MEP Marietje Schaake. “I did not know whether this decision was made by a human or whether this was the result of an automated decision,” the Dutch politician told WIRED.

The incident, while quickly resolved – the Google-owned company reinstated it and publicly apologised on Twitter the next day – is part of an increasing catalogue of uncertainty around algorithms making judgement decisions. (Google later contactedSchaake to say one of its algorithms did not behave as it was meant to and classified the video as spam, caused by a ‘rule’ in the algorithm making a mistake). As machine intelligence becomes more ubiquitous, there will be systems controlling online services and those that have an impact on the physical world.

The former currently includes: Netflix recommendations based on AI and algorithms; Google ranking news articles based on its code; and Facebook’s News Feed being controlled by machine learning. While at the most impactful end of the scale is the artificial intelligence behind driverless cars that will one day have to make moral decisions: in an inevitable crash, is the life of a human driver or the person in the path of the car more valuable?

Life-threatening or not, the algorithms, artificial intelligence and machine learning operating away from public view (Forrester predicts AI investment will grow 300 per cent in 2017) are increasingly being questioned. Technologists, politicians and academics have all called for greater transparency around the systems used by dominant tech firms.

“When algorithms affect human rights, public values or public decision-making we need oversight and transparency,” Schaake said. “The rule of law and universal human rights,” need to be baked into the systems of large technology companies. It’s even an issue garnering attention at the highest levels, German chancellor Angela Merkel has been the highest office holder to call for less secrecy.

“It’s a distinct problem,” Ben Wagner, director at the Centre for Internet and Human Rights told WIRED. “More and more social media platforms are using various different forms of automation in different ways that limit people’s ability to express themselves online.” The issue has been particularly highlighted with Facebook’s dissemination of fake news. In response, Facebook is building “better technical systems” to detect fake news before it spreads – although it’s unclear how these would work.

Wagner said the first step in a process to transparency – which will take many years, he insists – should be knowing whether or not a human or machine is making decisions online. “Because of the power of these platforms, they have an incredible ability to shape public opinion and to influence debates and yet their policies on taking down information or removing information are extremely opaque or difficult to make accountable to an outsider.”

Mike Ananny, an assistant professor of communication and journalism at the University of Southern California, agrees. He said a “deeper and broader” conversation about how algorithms are “reflections of who does or doesn’t have power” is needed. Something highlighted by Facebook’s critics. But how should companies and public sector organisations go about making their automated decisions more transparent and accountable?

“The primary challenges are: helping people see that algorithms are more than code; that transparency is not the same as accountability; and that the forces driving algorithmic systems are so dynamic, complex, and probabilistic that it makes little sense to talk about the algorithm as if it’s a single piece of code that isn’t constantly changing, that means different things to different people,” Ananny told WIRED.

Wagner added it isn’t just private companies faced with the challenges of increased reliance on machine-based decision making; automated systems are increasingly being used within public sector organisations too.

The UK government, seemingly, agrees. An artificial intelligence report for policy makers, (published by the Government Office for Science) says data used within automated systems should be carefully scrutinised before being handed over to AI. “Algorithmic bias may contribute to the risk of stereotyping,” the report says.

It warns: “Most fundamentally, transparency may not provide the proof sought: simply sharing static code provides no assurance it was actually used in a particular decision, or that it behaves in the wild in the way its programmers expect on a given dataset.”

Procedural regularity (the consistent application of algorithms), or use of a distributed ledger (in the way the Blockchain works) are mooted as possible ways to monitor algorithms. Schaake added there is “no silver bullet” to the problems raised by the issues. “Different levels of regulatory scrutiny are needed depending on the context,” she continued. The UK government report also says machine learning could be used to “spot inconsistent or anomalous outcomes” in other algorithms. This approach would see machine learning scan other algorithms and processes to look for mistakes or errors being introduced. But machine learning poses its own set of challenges.

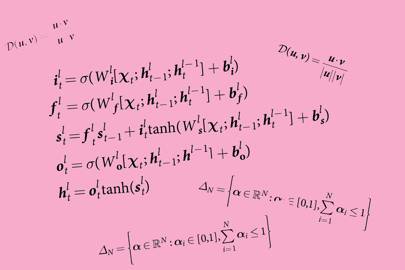

“They are very difficult to interrogate and interpret,” computer and information science professor Byron Wallace told WIRED. He explained that multi-layer neural networks are complex to understand as the use of “hidden” layers means it is “difficult to understand the (complex) relationship between inputs and outputs.” Yet, work is being done in the area.

MIT’s computer scientists have created a way for neural networks to be trained so they can provide rationale for their decisions. In the tests, the neural networks were able to extract the text and also use images from medical professionals to say what the diagnosis was, providing a reasoning for why it concluded the diagnosis was made. Wallace said this should be required “if a prediction [from AI] is somehow going to impact my life”.

In the work, the MIT researchers taught neural networks, using textual data, to explain the basis for a diagnosis from breast biopsies. As multiple companies try to “solve” cancer and diganose patients with machine learning and AI, the issue is set to become more pertinent.

As it does, organisations are considering what can be done. The questions of transparency and accountability are some the Partnership on AI, OpenAI, and the UK’s new Future Intelligencecentre could take on. The Partnership on AI is a collaboration between Facebook, Google, Microsoft, IBM and Amazon that aims to increase the transparency of algorithms and automated processes. “One of the roles we might play is propagating best practice, displaying some benchmarks, make available some datasets,” DeepMind’s Mustafa Suleyman said when the group launched in September.

While research is done, Schaake said firms developing automated decision technologies can start by “considering the values and desired results in the design phase” to ensure the public interest is included in their systems. For this to work, Ananny added there must be a broad interpretation of what an algorithm is: “the social, cultural, political, and ethical forces intertwined with them” should be considered too.

Wagner explained it is likely innovation within the area, despite governments being interested, will come from the private sector. But, if nothing is done? “The long-term consequences will be [fewer] people having more and more power over things in a very un-transparent and unaccountable way.”

[Source:- Wired]b