San Francisco’s school board has spent the past year in the national spotlight, garnering the attention of pundits from Fox News to the New York Times editorial pages for its controversial decisions on distance learning, school renamings and admissions policies.

The campaign to recall board members Alison Collins, Gabriela López and Faauuga Moliga, however, has relied on a donor network close to home.

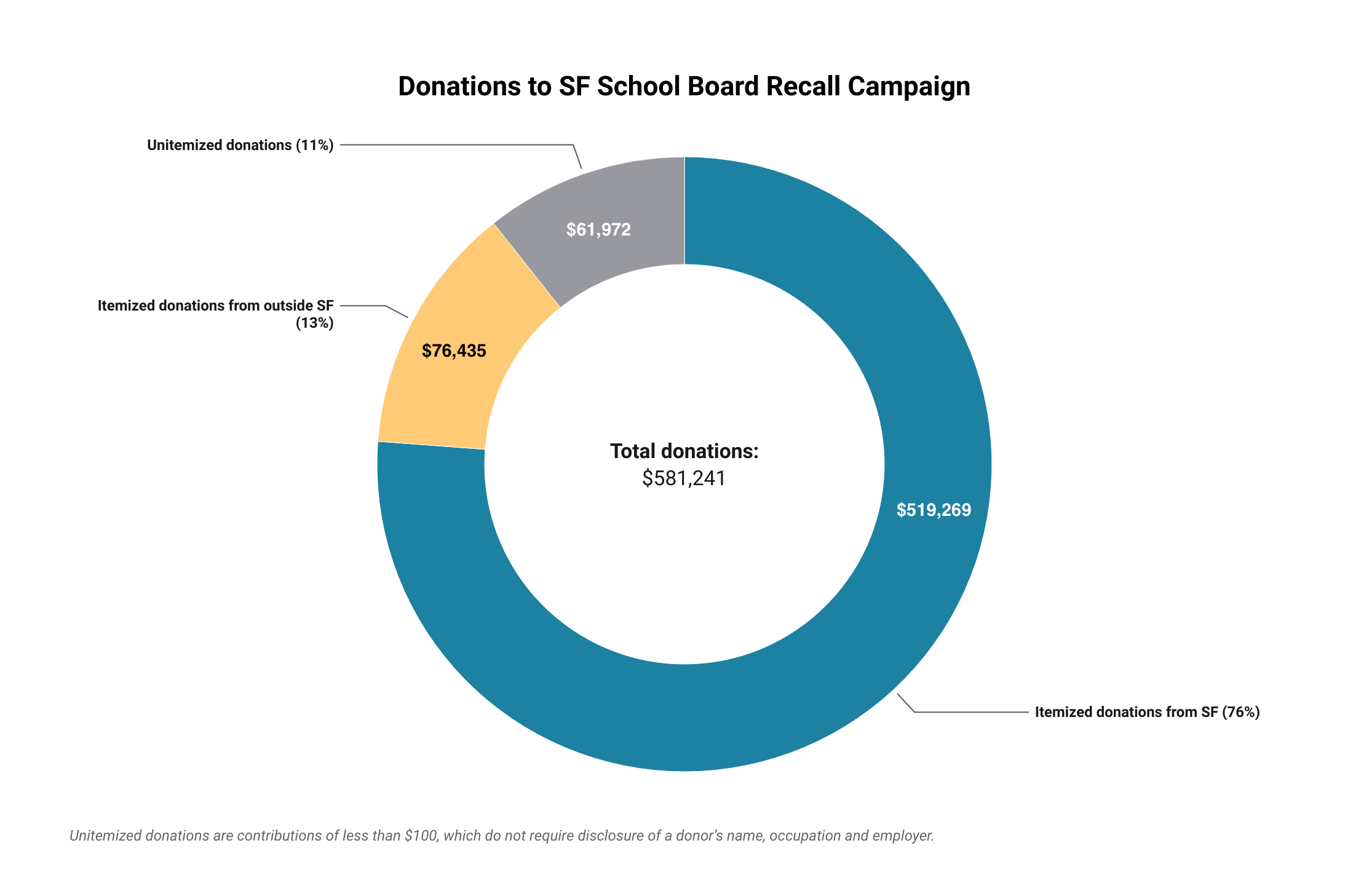

A KQED analysis of campaign filings for the election, slated for Feb. 15, found that at least 76% of the pro-recall cash raised so far is coming from donors in San Francisco.

Opponents of the recall, who haven’t started fundraising, will likely seek to portray the campaign as spearheaded by forces outside of the city — as has been the case in a number of other recent school board protests across the country — said Jason McDaniel, associate professor of political science at San Francisco State University, who reviewed KQED’s findings.

“I suspect they’ll still do that message, but I do think that so far the fact that most of the donations … are coming from people in San Francisco who are individuals will at least be a counterargument to that,” he said.

‘Local networks’

But the campaign finance reports filed with the city do reveal some potential political vulnerabilities for the recall campaign: Its top donors are wealthy venture capitalists who could serve as prime foils for the unions likely to bankroll the imperiled board members.

But the recall campaign, at least initially, appears to be more of an “amateur affair” than an orchestrated big money takeover of San Francisco schools, McDaniel said.

“I don’t mean that in an insulting way. There’s not maybe a ton of political experience there,” he added. “But what that seems to be is that they’re turning to their local networks. … That’s where they’re getting their contributions from so far. I suspect that’s pretty politically smart as well.”

Of the $581,240 raised by the recall committee through the end of September, at least $442,834 (76%) came from donors in the city, compared to at least $76,435 (13%) from outside of San Francisco. The remaining 11% of contributions were under $100 — classified as unitemized — meaning the donors did not have to disclose their names or location.

By comparison, some 63% of the donations made to candidates running for school board last year originated in San Francisco, and local measures on the ballot last November got 60% of their cash from city donors.

“The vast majority of donors actually are just from our community,” said Siva Raj, a San Francisco public school parent who is co-chair of the recall campaign. “These are parents, teachers.”

William Hack, who spent 31 years working for the San Francisco Unified School District as a teacher, principal and department supervisor, said he kicked in $75 and volunteered to gather signatures.

“I’ve never seen a board like this one,” he said, “and I’ve been through, over my years in the district, many school board meetings.”

Hack said the controversy surrounding school board Commissioner Alison Collins’s tweets, which included derogatory comments about Asian people, moved him to action, but he has plenty of other gripes. And while he fundamentally backed the board’s controversial effort to rename schools and overhaul the admissions policy to increase diversity at Lowell High School, he questioned the timing and handling of both initiatives.

“I do not typically ever support recalls, but this is different,” Hack said. “There needs to be a lesson here about their ongoing behavior and refusal to listen to the stakeholders in our city.”

In some instances, national press coverage of the school board’s recent controversies is helping to bring in money from across the country.

Mark Dalzell of Dover, New Hampshire, has no personal ties to the district. He said he chipped in $500 after reading about the issue this summer in The Wall Street Journal. For him, it’s ideological.

For years Dalzell chaired the board of a Los Angeles charter school and said he grew frustrated with the district’s school board.

“I’ve always been interested in trying to get more advantages for kids in low-income areas,” he said, “and so I view San Francisco as representative of that.”

Venture capitalists top donor list

Some of the recall’s biggest donors also have a history of involvement with education policy and politics.

The top two donors, Arthur Rock and David Sacks, have each put in $49,500. Rock, a self-employed venture capitalist with a record of funding education-related causes, has contributed to organizations with ties to charter schools, including political advocacy arms of the California Charter Schools Association, and the EdVoice for the Kids political action committee. Sacks, a fellow venture capitalist who runs Craft Ventures, contributed $180,000 to the campaign to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom and recently hosted a fundraiser in San Francisco for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Of the top 10 contributors so far to the SF school board recall campaign — all of whom have given at least $10,000 — six identified as partners or investors at venture capital firms.

In his campaign against the gubernatorial recall earlier this year, Newsom frequently invoked the donors of the campaign to oust him (including former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee and the Republican National Committee) as he attempted to tar the effort as out of step with the majority of California voters.

Similarly, the three school board members facing removal could point to the recall’s top donors as symbols of the city’s financial elite attempting to strong-arm a local election.

“What it tells me is that so many of the people who live in San Francisco who are wealthy happen to come from that world,” McDaniel said. “I do think that’s a potential vulnerability in terms of a political message. But right now, it does not feel like a very credible one.”

But venture capitalists aren’t the only big spenders. The Chinese American Democratic Club of San Francisco kicked in $10,000. CADC opposed the change to the Lowell admissions policy, but CADC Education Committee Chair Seeyew Mo says the group’s decision to donate was solely prompted by Collins’s tweets.

“This is not about a policy disagreement in terms of Commissioner Alison Collins. This is about rooting out anti-Asian sentiment and ideology from public education,” Mo said, pointing out that many CADC members volunteered to collect signatures to recall Collins. “A lot of the grassroots movement that you heard about, a lot of them are Chinese Americans who have not been politically active until this.”

CADC will announce its position on the recall of Lopez and Moliga after holding a membership vote, Mo said.

A group called San Francisco Common Sense Voter Guide, a committee supporting the recall of SF District Attorney Chesa Boudin, contributed $9,000 to the school board recall. That committee receives much of its funding from another political group called Neighbors for a Better San Francisco Advocacy, which is funded by a handful of wealthy San Francisco investors.

Dropping self-imposed donation limits

Initially, the recall campaign placed a $99.99 cap on donations, even though there’s no legal limit on fundraising for this type of campaign. It was an attempt, leaders said, to prevent any donor from having an outsize voice in the campaign.

But there were practical reasons, too: Contributions under $100 don’t require record-keeping, which campaign leaders expected they’d have to do themselves and “didn’t want to screw it up,” said campaign co-chair Autumn Looijen, a San Francisco resident whose children live in Los Altos.

The self-imposed limit was later increased significantly, to $49,500, to fund paid signature gatherers. State law requires donations of $50,000 or more to be printed on the paper petitions, which Looijen said would leave less space for signatures.

In all, the campaign raised $61,971 in small-dollar donations (under $100). The balance between smaller and larger donations indicates strong grassroots support, said political consultant Larry Tramutola, though he added that larger donations are vital for building a campaign’s infrastructure and legitimacy.

“Bigger contributions help you to get smaller contributions,” he added. “No one, even if they don’t like the school board, is going to give $100 dollars, $200, if they feel it’s a losing effort.”

Since the recall campaign eschewed its cap on larger contributions, the stream of donations under $100, typically a good barometer for grassroots engagement, has tailed off. The campaign reported raising $49,934 in unitemized donations through May 31, and just $12,038 since then.

The other side

Meanwhile, the campaign in support of Collins, Lopez and Moliga is just beginning to emerge.

Recall opponents launched their own effort last week, calling themselves NoSchoolBoardRecall, a self-described “group of parents, educators, and concerned SF residents who care about the needs of our public schools.”

The city’s teachers union, United Educators of San Francisco, is not involved in that campaign, though it is opposed to the recall, said its president, Cassondra Curiel. Instead, union leaders have said they are currently focused on member and community education.

“Our goal is to educate the community around why this recall is a waste of resources that should be spent on schools and is the first step on a path toward an ill-advised mayoral controlled school district,” Curiel said in a statement.

Curiel sees it as linked to the wave of recalls across the country — Ballotpedia has tracked 84 school board recall efforts so far this year, the highest tally on record. Meanwhile, the California School Boards Association counts roughly 60 efforts in the state alone.

On Monday, a political campaign committee called “Stop the Recall of Faauuga Moliga” filed with the city, an indication that the embattled board members may end up raising money separately.

Ultimately, Tramutola said, unions will provide the big money against the recall. And he said the local teachers union will likely flex its influence with the city’s Democratic clubs, which hold major sway with voters.

With the recall on the ballot, he said, the real fundraising will begin.

“This is far from a done deal. It’s a lot easier collecting signatures for a recall than to recall someone,” he said. “So I expect a battle royal.”

[“source=kqed”]