A string of horrifying climate-related disasters has brought a distinctly environmental theme to many people’s New Year resolutions.

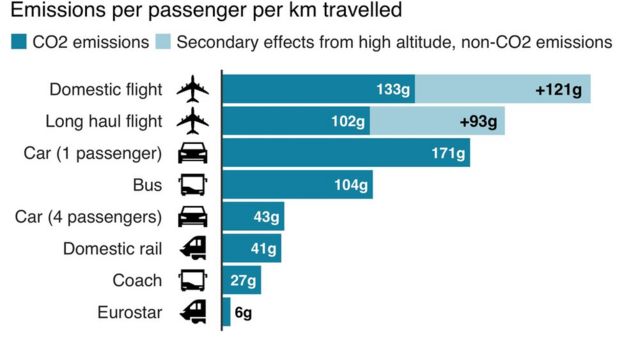

Many have chosen to reduce their carbon footprint by flying less, or cutting out planes completely. Flygskam – the Swedish word for “flight-shame” – has become commonplace.

In August, Swedish climate change campaigner Greta Thunberg set an example by crossing the Atlantic in a zero-emissions yacht.

If she had made the return journey from the UK to New York by air, she would have emitted 11% of the average annual emissions for someone in the UK, or the total caused by someone living in Ghana for a year.

The aviation industry contributes about 2% of the world’s carbon emissions, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and this is predicted to rise, with air passenger numbers expected to double by 2037.

More than 22,500 people have pledged to go flight-free in 2020, but in Europe, where cheap air travel reigns supreme, it’s not an easy decision to make.

Some governments are getting on board with flygskam and introducing measures to promote train travel.

Last week, Germany announced it would cut long distance rail fares by 10% – the first price decrease in 17 years.

Austria’s new green/conservative coalition has promised to expand its rail network and increase the tax on flights – a step towards meeting its target to be carbon-neutral by 2040.

Many of Europe’s night train services have gradually been phased out, but Sweden plans to reintroduce a sleeper service to the European mainland.

And this summer, Luxembourg will be the first country to make all public transport free, in a bid to reduce traffic congestion in cities.

Why take a long train journey when you can fly?

Train travel may take longer, but converts say it is a far more enriching experience than flying.

When Elias Bohun, who lives in Vienna, Austria, finished school, he was desperate to travel around South-East Asia. However, his environmental conscience stopped him booking a flight.

Instead, the 19-year-old and his girlfriend travelled to Vietnam overland.

“It was the most exciting experience I’ve ever had in my life”, says Elias.

Image copyrightELIAS BOHUN

Image copyrightELIAS BOHUNThe couple travelled from Vienna to Poland, Russia, Kazakhstan and China before arriving in Hanoi. They slept on night trains, then in the mornings left their luggage at the station and spent the day wandering around whatever city they found themselves in, before returning to board another sleeper.

Elias said he met more local people during that 16-day journey than the whole four-and-a-half months he spent travelling around South-East Asia.

“In trains, people have time, they really want to get to know you,” he said. “In hostels, you are always around tourists.”

It’s a romantic vision of a holiday, but surely only when you are young, with no commitments?

Not necessarily. Mary Penman, who is British but lives in Austria, makes the train journey back to the UK at least once a year with her husband and two small children. She stopped flying several years ago as a result of flygskam.

Image copyrightMARY PENMAN

Image copyrightMARY PENMANFrom Vienna, the family gets the night train to Cologne and then to Brussels, where they change onto the Eurostar to London. Mary says it takes two days and costs about €117 (£100, $130) one way if booked in advance – €200 at shorter notice.

She concedes that a long train journey with two toddlers in tow is “complicated, but with children, even going to the shops is complicated”. She prefers it to the claustrophobic stress of an airport.

And in many countries, children aged under six travel for free.

Last year, the family went on holiday to Venice by train. Her older son spent the journey playing with children from other families on board.

“It’s like a travelling village,” says Mary. “There’s a real camaraderie among the families on board.”

Not a fair competition

Although many would prefer to travel by rail, the cost is often prohibitive. A Eurostar train from London to Paris emits up to 90% less carbon than flying, but a ticket generally costs twice as much.

Customers are also put off by planning a rail journey between different countries.

“People don’t want to put time into planning their holidays,” says Elias. “It’s difficult and expensive to organise train journeys within Europe.”

This was why he and his father, Mathias, set up Traivelling, a travel agency which provides holidays purely on trains.

Traivelling offers a return train journey from London to Lisbon that costs €350, but a quick look online brings up budget flights at €86. A single train ticket from Copenhagen to Rome would cost €110, but some flights are priced at less than €20.

Matthias and Elias agree that it is difficult for trains to compete with flying in terms of price and frequency. Although there has been an increase in high-speed trains, these are extremely expensive compared with the hundreds of cheap flights between major airports every day.

“The offer is too good compared to trains,” says Matthias.

A shift in mindset

While cost and time are huge factors, it seems replacing planes with trains requires a shift in mindset.

Rather than chunking together leave in a two-week holiday, the rise in budget air travel has caused a rise in shorter, more frequent breaks.

Some companies have encouraged their employees to use more carbon-friendly modes of travel that take more time, by introducing “climate perks”.

WeiberWirtschaft, a women’s co-operative in Berlin that supports female entrepreneurs, has told its workers they can have three days’ additional leave if they abstain from flying for a year.

Image copyrightELIAS BOHUN

Image copyrightELIAS BOHUNElias’s father Mathias remembers a time when it was normal to spend a few weeks travelling by train to Greece or France.

“We were educated to forget this,” he says. “We are now thinking that the only way to have a good experience is by taking a plane and going somewhere far and fast.”

Elias thinks the opposite is true.

“If you take the train to Vietnam, you start to understand the world is huge,” he says.

Mary says while trains take longer, “the journey becomes part of the holiday, rather than just being a way of getting you somewhere”.

[“source=bbc”]