he refugee crisis has seen schools in many countries having to accommodate new arrivals. But the OECD’s education director, Andreas Schleicher, says the evidence of international tests suggests migrants are as likely to become an asset to their new schools rather than a problem.

Immigrant children are often highly motivated and have ambitious parents. And these clever, hungry-to-learn youngsters often achieve higher results than the rest of their classmates.

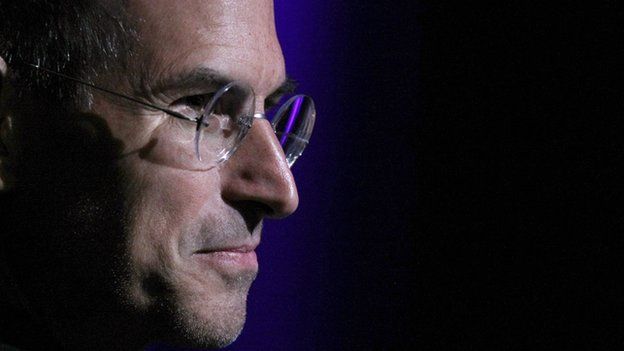

In 1954, the United States opened its borders to an immigrant from Syria.

His son, Steve Jobs, became one of the most creative entrepreneurs, revolutionising industries from personal computers through animated movies and music to mobile phones and digital publishing.

In the current refugee crisis that might look like a fairy-tale, but it is not that implausible.

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesWhile immigrant youngsters might face cultural, social and economic disadvantages, the top 10% of 15-year-old students with an immigrant background in the United States did just as well as the top 10% without an immigrant background, as measured by the international Pisa tests.

In fact, when accounting for social background, these high-achieving immigrant teenagers were almost a school year ahead.

This doesn’t only happen in the United States. In 13 out of the 37 countries with comparable data, including the United Kingdom, the top 10% of immigrants were at least 10 points ahead of their non-immigrant counterparts in Pisa tests, after accounting for social background.

These highly motivated students, managing to overcome the double disadvantage of poverty and an immigrant background, have the potential to make exceptional contributions to their host countries.

Image copyrightAP

Image copyrightAPOn average across all countries, top performing immigrants and non-immigrants reached similar levels of performance on the Pisa mathematics test.

Many immigrants, after the sacrifices of migrating, seem determined to make the most of any opportunity that arises.

| How migrant pupils achieve compared with non-migrant, among top 10% in test results | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pupils with a migrant background | Migrants and non-migrants, gap in test results | |

| Canada | 30% | +9 Migrants achieve higher |

| Finland | 3% | -57 Migrants achieve lower |

| France | 15% | -25 Migrants achieve lower |

| Germany | 13% | -28 Migrants achieve lower |

| Hong Kong | 35% | +13 Migrants achieve higher |

| Italy | 8% | -25 Migrants achieve lower |

| New Zealand | 26% | +13 Migrants achieve higher |

| Singapore | 18% | +11 Migrants achieve higher |

| Sweden | 15% | +8 Migrants achieve higher |

| Switzerland | 24% | -35 Migrants achieve lower |

| United Kingdom | 13% | +10 Migrants achieve higher |

| United States | 22% | +7 Migrants achieve higher |

| United Arab Emirates | 55% | +75 Migrants achieve higher |

| Source: OECD, based on 15 year olds taking Pisa tests | ||

Their children also seem ready to take on an academic challenge. Alongside the Pisa tests are questions about students’ willingness to try to solve more complex problems. First-generation immigrants, including in the UK, are more likely than average to want to stretch themselves and try to answer more difficult problems.

The OECD’s research shows that immigrant students – and their parents – hold an ambition to succeed that in most cases matches, and in some cases surpasses, the aspirations of families in their host country.

More stories from the BBC’s Knowledge economy series looking at education from a global perspective and how to get in touch

For example, parents of immigrant students in Belgium, Germany and Hungary are more likely to expect that their children will go to university and get a degree than parents of students without an immigrant background.

What makes this so remarkable is that these immigrant families are likely to be poorer than their non-migrant neighbours and their children are likely to do less well in school. But nonetheless their parents still hold higher expectations for them.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAThe gap in parental expectation grows even wider when it’s a comparison between newly-arrived poor migrants and local deprived families.

In Belgium, Germany, Hong Kong and Hungary, the parents of immigrant students hold much higher educational expectations for their children than the parents of similarly disadvantaged non-immigrant students.

The migrant students seem to be more determined. Comparing students of similar ability, the immigrant teenagers were often the ones with more ambitious career expectations.

Such confidence can pay off. Students who hold ambitious, yet realistic expectations about their educational prospects are likely to work harder and make better use of the education opportunities available to them.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPANonetheless many children from immigrant backgrounds face enormous challenges at school.

They need to adjust quickly to different academic expectations, learn in a new language, forge a social identity that incorporates both their background and their adopted country – while often under conflicting pressures from family and peers.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAThese difficulties in integrating into a new society are magnified when immigrants are segregated into poor neighbourhoods and into struggling schools.

So it’s no surprise that Pisa test results have shown students with an immigrant background falling behind non-immigrant students.

However, this average performance gap should not mask the finding that many immigrant students overcome these obstacles and excel academically. They succeed in school and it’s a testament to the great drive, motivation and openness that they and their families possess.

Image copyrightAP

Image copyrightAPThere is also nothing inevitable about immigrant students doing less well, as the evidence of Pisa tests shows they can achieve very different results in different countries.

The crunch point isn’t the point of entry for migrant students, but what happens afterwards. It depends on whether schools are ready and able to help such migrants succeed and reduce the disadvantages that will face them.

The world might seem to be becoming an increasingly complex and uncertain place, but some immigrant students are an inspiration for how societies can become more cohesive and resilient.

[Source:- BBC]