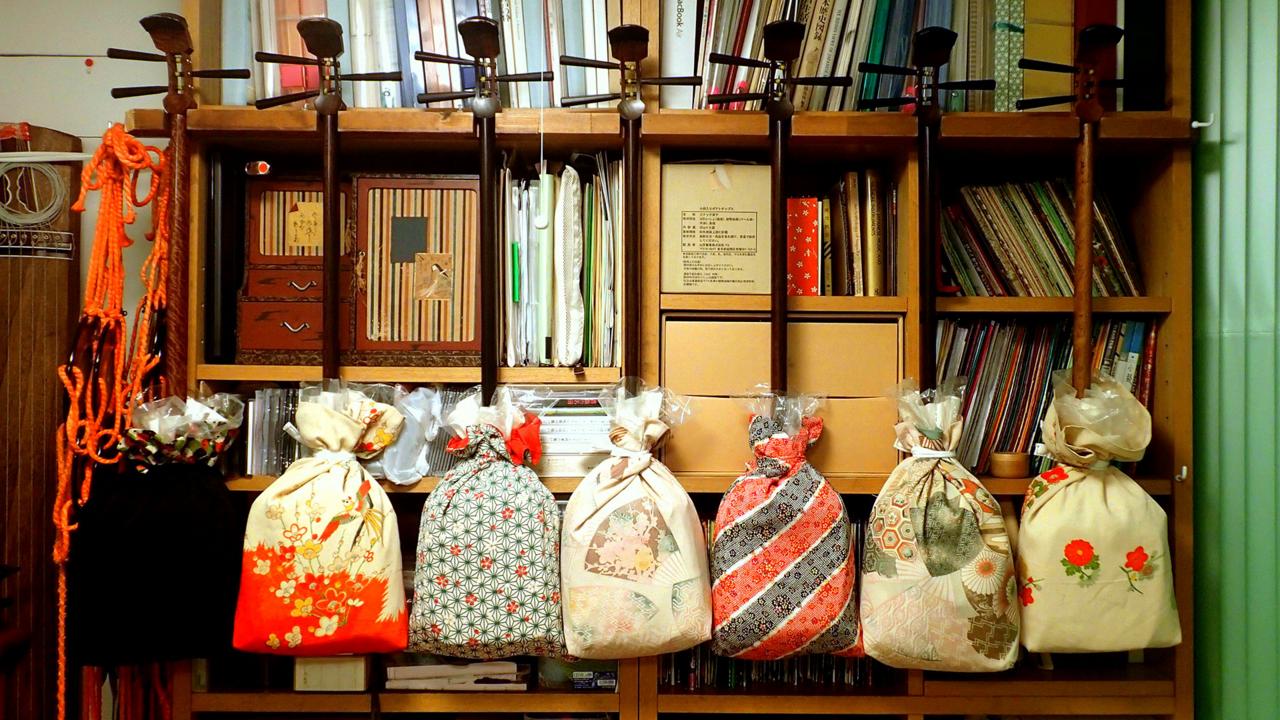

In Tokyo’s Meguro ward, Makoto Nishimura’s small apartment is a trove of traditional Japanese instruments. Hanging in front of her bookshelf is a row of three-stringed shamisen (a type of square-shaped lute) wrapped elegantly in kimono fabric. Other instruments used for kabuki performances – such as flutes, drums and a 13-stringed Japanese harp called a koto – sit off to the side in and around the bookshelf. But just like in a kabuki ensemble, the shamisen take centre stage.

Shamisens hang on the walls of Nishimura’s eclectic apartment (Credit: Celia Knox)

Nishimura’s first encounter with a shamisen was as a 17-year-old high school student when her mother took her to meet Hiroaki Kikuoka, a well-known music professor. Kikuoka encouraged her to take up the instrument and mentored Nishimura for more than 25 years – even offering free shamisen lessons as she struggled as a working mother of two. This kindness inspired a strong sense of gratitude within Nishimura, and she soon opened a home studio to pass her knowledge of kabuki music on to future generations.

The shamisen is the most iconic instrument in kabuki music (Credit: Islandstock/Alamy)

Though modern acts like the Yoshida Brothers have updated shamisen’s image, the art is slowly disappearing as young Japanese gravitate towards pop music. The few professional shamisen musicians left today mainly come from families where the skill is handed down from generation to generation, and children start learning as early as six or seven years old.

Interestingly, Nishimura has seen the most interest from foreigners. In fact, one of her first shamisen students was an Australian. “It’s very ironic,” she writes on her studio’s website. “My foreign students are more Japanese than most Japanese.”

Over the next 20 years, Nishimura’s list of kabuki music students would surpass 200. Today, her clientele comes from Germany, Brazil, France, South Africa, England, Poland, Canada and the US.

In the evenings and on the weekends, Nishimura’s apartment fills with the sound of students plucking, whistling and singing. Once a year (most recently this past August), she holds a concert produced with the fees collected from the lessons. Her students dress in full kimono and play – accompanied by professional musicians – for audiences of more than 100 people.

Clad in blue, Nishimura falls to the back and lets her students take centre stage

(Credit: Learning Shamisen)

For visitors who can’t attend Nishimura’s concerts, there are several other opportunities to see the shamisen played live in Tokyo’s kabuki venues. Nishimura recommends the newly renovated Kabukiza in the city’s Ginza district. The actors – all men – dress in elaborate costumes and wigs, and cover their faces with dramatic makeup. As they sing and dance – telling tales of love, family and war – the shamisen and other instruments add sound effects to emphasise the characters’ various emotions.